پیشنویس:تغییر اقلیم

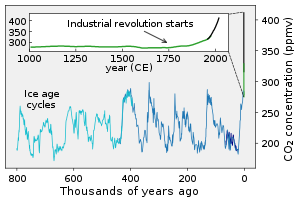

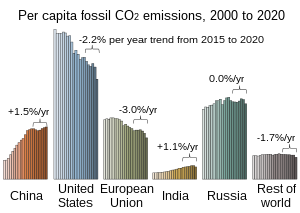

در استفاده متداول، «تغییر آب و هوا»، «گرمایش جهانی» —افزایش مداوم میانگین دمای جهانی—و تأثیرات گستردهتر آن بر سامانه اقلیمی زمین را توصیف میکند. تغییرپذیری و تغییر اقلیم همچنین شامل تغییرات طولانی مدت قبلی در آب و هوای زمین میشود. افزایش فعلی در دمای متوسط جهانی اجماع علمی درباره تغییر اقلیم است، به ویژه سوزاندن سوخت فسیلی از زمان انقلاب صنعتی است.[۳][۴] استفاده از سوخت فسیلی، عملهای جنگلزدایی و تغییر اقلیم، و برخی نشر گازهای گلخانهای در کشاورزی و آثار زیستمحیطی بتن را آزاد میکنند.[۵] این گازها اثر گلخانهای که زمین تابش گرمایی پس از آن از نور خورشید گرم میشود، پایینترین جو را گرم میکند. کربن دیاکسید، گاز گلخانهای اولیه که باعث گرم شدن زمین میشود، کربن دیاکسید در اتمسفر زمین است و در سطوحی است که برای میلیونها سال دیده نشده است.[۶]

تغییرات آب و هوایی بهطور فزاینده ای تأثیرات تغییر اقلیم بزرگ است. بیابانزایی، در حالی که موج گرماها و آتشسوزی جنگلها رایجتر میشوند.[۷][۸] گرمایش تقویت شده در قطب شمال به ذوب شدن کمک کرده است پایایخبندان، عقبنشینی یخچالهای طبیعی از سال ۱۸۵۰ و کاهش دریایخ شمالگان.[۹]دماهای بالاتر نیز باعث چرخندهای حارهای و تغییر اقلیم، خشکسالی و سایر هوای غیرعادی میشوند.[۱۰]تغییر سریع محیطی در بومسازگان کوهستانی، صخرههای مرجانی و تغییر اقلیم در شمالگان بسیاری از گونهها را مجبور به جابجایی یا خطر انقراض از تغییر اقلیم میکند.[۱۱] حتی اگر تلاشها برای به حداقل رساندن گرمایش آینده موفقیتآمیز باشد، برخی از اثرات برای قرنها ادامه خواهد داشت. اینها عبارتند از: گرمایش اقیانوس، اسیدی شدن اقیانوس و زایش سطح آب دریاها.[۱۲]

تغییر اقلیم مردم را تهدید میکند با افزایش سیل، افزایش گرمای شدید، غذا و کمبود آب، افزایش بیشتر بیماری، و تحلیل اقتصادی تغییرات اقلیمی. مهاجرت اقلیمی و تعارض هم میتواند در نتیجه باشد.[۱۳] سازمان جهانی بهداشت]] تغییرات اقلیمی را یکی از بزرگترین تهدیدات بهداشت جهانی در قرن بیست و یکم مینامد.[۱۴] جوامع و اکوسیستمها بدون کاهش تغییر اقلیم خطرات شدیدتری را تجربه خواهند کرد.[۱۵] سازگاری با تغییر اقلیم از طریق تلاشهایی مانند مهار سیل اقدامات یا خشکیرست تا حدی خطرات تغییرات اقلیمی را کاهش میدهد، اگرچه برخی از محدودیتها به سازگاری با تغییر اقلیم قبلاً رسیدهاند.[۱۶][۱۷] برای زمینهها، بخشها و مناطق خاص مستند شده است (اعتماد بالا)... محدودیتهای نرم برای سازگاری در حال حاضر توسط کشاورزان و خانوادههای کوچک در امتداد برخی مناطق ساحلی کم ارتفاع (اعتماد متوسط) که ناشی از مالی، حکومتی، نهادی و محدودیتهای سیاست (اعتماد بالا). برخی از اکوسیستمهای استوایی، ساحلی، قطبی و کوهستانی به محدودیتهای سازگاری سخت (اعتماد بالا) رسیدهاند. سازگاری حتی با سازگاری مؤثر و قبل از رسیدن به محدودیتهای نرم و سخت (اعتماد بالا) جلوی همه زیانها و آسیبها را نمیگیرد. بیشترین آسیبپذیر در برابر تغییرات اقلیمی هستند.[۱۸][۱۹]

بسیاری از تأثیرات تغییرات آب و هوایی در سالهای اخیر احساس شده است، به طوری که سال ۲۰۲۳ از زمان شروع ردیابی منظم در سال ۱۸۵۰، گرمترین سال با +۱٫۴۸ تغییر درجه سلسیوس (۲٫۶۶ تغییر درجه فارنهایت) بوده است.[۲۱][۲۲]

گرم شدن اضافی این تأثیرات را افزایش میدهد و میتواند نقطههای عطف سامانه اقلیمی را آغاز کند، مانند ذوب همه یخسار گرینلند.[۲۳]

بر اساس توافق پاریس ۲۰۱۵، کشورها بهطور جمعی توافق کردند که گرمایش را «زیر ۲ درجه سانتیگراد» حفظ کنند. با این حال، با تعهداتی که تحت این توافقنامه داده شده است، گرمایش جهانی همچنان تا پایان قرن به حدود ۲٫۸ تغییر درجه سلسیوس (۵٫۰ تغییر درجه فارنهایت) خواهد رسید.[۲۴]محدود کردن گرمایش به ۱٫۵ درجه سانتیگراد مستلزم کاهش انتشار گازهای گلخانه ای تا سال ۲۰۳۰ به نصف و دستیابی به انتشار خالص صفر تا سال ۲۰۵۰ است.[۲۵][۲۶]

حذف سوختهای فسیلی توسط نگهداری انرژی و تغییر به منابع انرژی که آلودگی کربنی قابل توجهی تولید نمیکنند. این منابع انرژی عبارتند از انرژی بادی، برق خورشیدی، انرژی آبی و انرژی هستهای.[۲۷][۲۸] برق تولید شده پاک میتواند جایگزین سوختهای فسیلی برای وسیله نقلیه الکتریکی، گرمایش الکتریکی و فرآیندهای صنعتی در حال اجرا شود.[۲۹] کربن همچنین میتواند حذف شدن از اتمسفر باشد، به عنوان مثال با حمایت جنگل و کشاورزی با روشهایی که گرفتن کربن در خاک.[۳۰][۳۱]

اصطلاحها

[ویرایش]قبل از دهه ۱۹۸۰ مشخص نبود که آیا اثر گرمایش اثر گلخانهای قویتر از ذرات معلق در آلودگی هوا است یا خیر. دانشمندان از اصطلاح «اصلاح ناخواسته آب و هوا» برای اشاره به تأثیرات انسان بر اقلیم در این زمان استفاده کردند.[۳۲] در دهه ۱۹۸۰، اصطلاحات «گرمایش جهانی» و «تغییر آب و هوا» رایج تر شدند و اغلب به جای یکدیگر استفاده میشدند.[۳۳][۳۴][۳۵] از نظر علمی، «گرمایش جهانی» تنها به افزایش گرمایش سطح اشاره دارد، در حالی که «تغییر اقلیم» هم گرمایش جهانی و هم اثرات آن بر روی زمین، مانند تغییرات بارندگی را توصیف میکند.[۳۲]

«تغییر آب و هوا» همچنین میتواند بهطور گستردهتری برای گنجاندن تغییرپذیری و تغییر اقلیم استفاده شود که در طول تاریخ زمین اتفاق افتاده است.[۳۶] «گرمایش جهانی» - در اوایل سال ۱۹۷۵ مورد استفاده قرار گرفت[۳۷]— در سال ۱۹۸۸ محبوبیت این اصطلاح پس شهادت دانشمند آب و هوا ناسا، جیمز هنسن، در مجلس سنای ایالات متحده آمریکا بیشتر شد.[۳۸] از دهه ۲۰۰۰، استفاده از «تغییر آب و هوا» افزایش پیدا کرده است.[۳۹] دانشمندان، سیاستمداران و رسانههای مختلف ممکن است از اصطلاحات «بحران اقلیمی» یا «اعلامیه اضطرار اقلیمی» برای صحبت در مورد تغییرات اقلیمی استفاده کنند یا به جای آن از اصطلاح «گرمایش جهانی» استفاده کنند.[۴۰][۴۱]

Global temperature rise

[ویرایش]Temperature records prior to global warming

[ویرایش]

Over the last few million years the climate cycled through دوره یخچالی. One of the hotter periods was the Last Interglacial, around 125,000 years ago, where temperatures were between 0.5 °C and 1.5 °C warmer than before the start of global warming.[۴۴] This period saw sea levels 5 to 10 metres higher than today. The most آخرین بیشینه یخچالی 20,000 years ago was some ۵–۷ °C colder. This period has sea levels that were over ۱۲۵ متر (۴۱۰ فوت) lower than today.[۴۵]

Temperatures stabilized in the current interglacial period beginning هولوسن.[۴۶] This period also saw the start of agriculture.[۴۷] Historical patterns of warming and cooling, like the دوران گرمایشی قرون وسطی and the عصر یخبندان کوچک، did not occur at the same time across different regions. Temperatures may have reached as high as those of the late 20th century in a limited set of regions.[۴۸][۴۹] Climate information for that period comes from پروکسی (اقلیم), such as trees and مغزه یخیs.[۵۰][۵۱]

Warming since the Industrial Revolution

[ویرایش]

Around 1850 دماسنج records began to provide global coverage.[۵۴] Between the 18th century and 1970 there was little net warming, as the warming impact of greenhouse gas emissions was offset by cooling from گوگرد دیاکسید emissions. Sulfur dioxide causes باران اسیدی، but it also produces سولفات aerosols in the atmosphere, which reflect sunlight and cause so-called تاریکشدن زمین. After 1970, the increasing accumulation of greenhouse gases and controls on sulfur pollution led to a marked increase in temperature.[۵۵][۵۶][۵۷]

Ongoing changes in climate have had no precedent for several thousand years.[۵۸] Multiple independent datasets all show worldwide increases in surface temperature,[۵۹] at a rate of around 0.2 °C per decade.[۶۰] The 2014–2023 decade warmed to an average 1.19 °C [1.06–1.30 °C] compared to the pre-industrial baseline (1850–1900).[۶۱] Not every single year was warmer than the last: internal تغییرپذیری و تغییر اقلیم processes can make any year 0.2 °C warmer or colder than the average.[۶۲] From 1998 to 2013, negative phases of two such processes, Pacific Decadal Oscillation (PDO)[۶۳] and Atlantic Multidecadal Oscillation (AMO)[۶۴] caused a so-called "global warming hiatus".[۶۵] After the hiatus, the opposite occurred, with years like 2023 exhibiting temperatures well above even the recent average.[۶۶] This is why the temperature change is defined in terms of a 20-year average, which reduces the noise of hot and cold years and decadal climate patterns, and detects the long-term signal.[۶۷]: 5 [۶۸]

A wide range of other observations reinforce the evidence of warming.[۶۹][۷۰] The upper atmosphere is cooling, because گاز گلخانهایes are trapping heat near the Earth's surface, and so less heat is radiating into space.[۷۱] Warming reduces average snow cover and عقبنشینی یخچالهای طبیعی از سال ۱۸۵۰. At the same time, warming also causes greater evaporation from the oceans, leading to more رطوبت، more and heavier بارش.[۷۲][۷۳] Plants are گل earlier in spring, and thousands of animal species have been permanently moving to cooler areas.[۷۴]

Differences by region

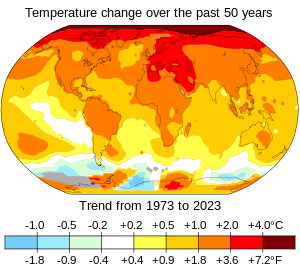

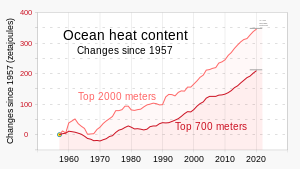

[ویرایش]Different regions of the world تغییرپذیری و تغییر اقلیم. The pattern is independent of where greenhouse gases are emitted, because the gases persist long enough to diffuse across the planet. Since the pre-industrial period, the average surface temperature over land regions has increased almost twice as fast as the global average surface temperature.[۷۵] This is because oceans lose more heat by تبخیر سطحی and oceans can store a lot of heat.[۷۶] The thermal energy in the global climate system has grown with only brief pauses since at least 1970, and over 90% of this extra energy has been stored in the ocean.[۷۷][۷۸] The rest has heated the اتمسفر، melted ice, and warmed the continents.[۷۹]

The نیمکره شمالی and the قطب شمال have warmed much faster than the قطب جنوب and نیمکره جنوبی. The Northern Hemisphere not only has much more land, but also more seasonal snow cover and دریایخ. As these surfaces flip from reflecting a lot of light to being dark after the ice has melted, they start سپیدایی.[۸۰] Local black carbon deposits on snow and ice also contribute to Arctic warming.[۸۱] Arctic surface temperatures are increasing between three and four times faster than in the rest of the world.[۸۲][۸۳][۸۴] Melting of یخسارs near the poles weakens both the Atlantic and the Antarctic limb of گردش دماشوری، which further changes the distribution of heat and بارش around the globe.[۸۵][۸۶][۸۷][۸۸]

Future global temperatures

[ویرایش]

The سازمان جهانی هواشناسی estimates there is an 80% chance that global temperatures will exceed 1.5 °C warming for at least one year between 2024 and 2028. The chance of the 5-year average being above 1.5 °C is almost half.[۹۱]

The IPCC expects the 20-year average global temperature to exceed +1.5 °C in the early 2030s.[۹۲] The ششمین گزارش هیئت بیندولتی تغییر اقلیم (2021) included projections that by 2100 global warming is very likely to reach ۱٫۰–۱٫۸ °C under a scenario with very low emissions of greenhouse gases, 2.1–3.5 °C under an intermediate emissions scenario, or 3.3–5.7 °C under a very high emissions scenario.[۹۳] The warming will continue past 2100 in the intermediate and high emission scenarios,[۹۴][۹۵] with future projections of global surface temperatures by year 2300 being similar to millions of years ago.[۹۶]

The remaining carbon budget for staying beneath certain temperature increases is determined by modelling the carbon cycle and حساسیت به اقلیم to greenhouse gases.[۹۷] According to برنامه محیط زیست سازمان ملل متحد، global warming can be kept below 1.5 °C with a 50% chance if emissions after 2023 do not exceed 200 gigatonnes of CO2 . This corresponds to around 4 years of current emissions. To stay under 2.0 °C, the carbon budget is 900 gigatonnes of CO2 , or 16 years of current emissions.[۹۸]

Causes of recent global temperature rise

[ویرایش]

The climate system experiences various cycles on its own which can last for years, decades or even centuries. For example, ال نینو–نوسان جنوبی events cause short-term spikes in surface temperature while ال نینو–نوسان جنوبی events cause short term cooling.[۹۹] Their relative frequency can affect global temperature trends on a decadal timescale.[۱۰۰] Other changes are caused by an همارزی تابشی زمین from اجبار تابشی.[۱۰۱] Examples of these include changes in the concentrations of گاز گلخانهایes, تابندگی خورشید، آتشفشان eruptions, and وادارنده مداری around the Sun.[۱۰۲]

To determine the human contribution to climate change, unique "fingerprints" for all potential causes are developed and compared with both observed patterns and known internal تغییرپذیری و تغییر اقلیم.[۱۰۳] For example, solar forcing—whose fingerprint involves warming the entire atmosphere—is ruled out because only the lower atmosphere has warmed.[۱۰۴] Atmospheric aerosols produce a smaller, cooling effect. Other drivers, such as changes in سپیدایی، are less impactful.[۱۰۵]

Greenhouse gases

[ویرایش]

Greenhouse gases are transparent to نور خورشید، and thus allow it to pass through the atmosphere to heat the Earth's surface. The Earth سرمای تابشی، and greenhouse gases absorb a portion of it. This absorption slows the rate at which heat escapes into space, trapping heat near the Earth's surface and warming it over time.[۱۱۱]

While بخار آب (≈50%) and clouds (≈25%) are the biggest contributors to the greenhouse effect, they primarily change as a function of temperature and are therefore mostly considered to be بازخورد تغییرات اقلیمی that change حساسیت به اقلیم. On the other hand, concentrations of gases such as CO2

(≈۲۰٪), ازون تروپوسفری،[۱۱۲] کلروفلوئوروکربن and نیتروز اکسید are added or removed independently from temperature, and are therefore considered to be اجبار تابشی that change global temperatures.[۱۱۳]

Before the انقلاب صنعتی، naturally-occurring amounts of greenhouse gases caused the air near the surface to be about 33 °C warmer than it would have been in their absence.[۱۱۴][۱۱۵] Human activity since the Industrial Revolution, mainly extracting and burning fossil fuels (زغالسنگ، نفت خام، and گاز طبیعی),[۱۱۶] has increased the amount of greenhouse gases in the atmosphere, resulting in a اجبار تابشی. In 2022, the کربن دیاکسید در اتمسفر زمین and methane had increased by about 50% and 164%, respectively, since 1750.[۱۱۷] These CO2

levels are higher than they have been at any time during the last 2 million years. متان موجود در جو are far higher than they were over the last 800,000 years.[۱۱۸]

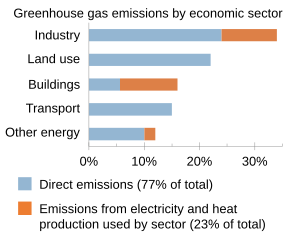

Global anthropogenic greenhouse gas emissions in 2019 were پتانسیل گرمایش جهانی 59 billion tonnes of CO2 . Of these emissions, 75% was CO2 , 18% was متان، 4% was nitrous oxide, and 2% was fluorinated gases.[۱۱۹] CO2

emissions primarily come from burning fossil fuels to provide energy for ترابری، manufacturing, گرما، and electricity.[۵] Additional CO2 emissions come from جنگلزدایی و تغییر اقلیم and فرایندهای صنعتی، which include the CO2 released by the chemical reactions for سیمان، کوره بلند، فرایند هال–هرولت، and فرایند هابر.[۱۲۰][۱۲۱][۱۲۲][۱۲۳] Methane emissions come from livestock, manure, برنج، landfills, wastewater, and coal mining, as well as oil and gas extraction.[۱۲۴][۱۲۵] Nitrous oxide emissions largely come from the microbial decomposition of کود.[۱۲۶][۱۲۷]

While methane only lasts in the atmosphere for an average of 12 years,[۱۲۸] CO2

lasts much longer. The Earth's surface absorbs CO2 as part of the چرخه کربن. While plants on land and in the ocean absorb most excess emissions of CO2 every year, that CO2 is returned to the atmosphere when biological matter is digested, burns, or decays.[۱۲۹] Land-surface مخزن کربن processes, such as تثبیت کربن in the soil and photosynthesis, remove about 29% of annual global CO2 emissions.[۱۳۰] The ocean has absorbed 20 to 30% of emitted CO2 over the last 2 decades.[۱۳۱] CO2 is only removed from the atmosphere for the long term when it is stored in the Earth's crust, which is a process that can take millions of years to complete.[۱۲۹]

Land surface changes

[ویرایش]

Around 30% of Earth's land area is largely unusable for humans (یخچال طبیعیs, بیابانs, etc.), 26% is جنگلs, 10% is درختچهزار and 34% is زمین کشاورزی.[۱۳۳] جنگلزدایی is the main کاربری سرزمین contributor to global warming,[۱۳۴] as the destroyed trees release CO2 , and are not replaced by new trees, removing that مخزن کربن.[۳۰] Between 2001 and 2018, 27% of deforestation was from permanent clearing to enable گسترش کشاورزی for crops and livestock. Another 24% has been lost to temporary clearing under the کشاورزی نوبتی agricultural systems. 26% was due to درختبری for wood and derived products, and آتشسوزی جنگلs have accounted for the remaining 23%.[۱۳۵] Some forests have not been fully cleared, but were already degraded by these impacts. Restoring these forests also recovers their potential as a carbon sink.[۱۳۶]

Local vegetation cover impacts how much of the sunlight gets reflected back into space (سپیدایی), and how much کولر آبی. For instance, the change from a dark جنگل to grassland makes the surface lighter, causing it to reflect more sunlight. Deforestation can also modify the release of chemical compounds that influence clouds, and by changing wind patterns.[۱۳۷] In tropic and temperate areas the net effect is to produce significant warming, and forest restoration can make local temperatures cooler.[۱۳۶] At latitudes closer to the poles, there is a cooling effect as forest is replaced by snow-covered (and more reflective) plains.[۱۳۷] Globally, these increases in surface albedo have been the dominant direct influence on temperature from land use change. Thus, land use change to date is estimated to have a slight cooling effect.[۱۳۸]

Other factors

[ویرایش]Aerosols and clouds

[ویرایش]Air pollution, in the form of ذرات معلق on a large scale.[۱۳۹] Aerosols scatter and absorb solar radiation. From 1961 to 1990, a gradual reduction in the amount of چگالی تابش was observed. This phenomenon is popularly known as تاریکشدن زمین,[۱۴۰] and is primarily attributed to سولفات aerosols produced by the combustion of fossil fuels with heavy sulfur concentrations like زغالسنگ and bunker fuel.[۵۷] Smaller contributions come from black carbon, organic carbon from combustion of fossil fuels and biofuels, and from anthropogenic dust.[۱۴۱][۵۶][۱۴۲][۱۴۳][۱۴۴] Globally, aerosols have been declining since 1990 due to pollution controls, meaning that they no longer mask greenhouse gas warming as much.[۱۴۵][۵۷]

Aerosols also have indirect effects on the همارزی تابشی زمین. Sulfate aerosols act as cloud condensation nuclei and lead to clouds that have more and smaller cloud droplets. These clouds reflect solar radiation more efficiently than clouds with fewer and larger droplets.[۱۴۶] They also reduce the growth of raindrops, which makes clouds more reflective to incoming sunlight.[۱۴۷] Indirect effects of aerosols are the largest uncertainty in اجبار تابشی.[۱۴۸]

While aerosols typically limit global warming by reflecting sunlight, black carbon in دوده that falls on snow or ice can contribute to global warming. Not only does this increase the absorption of sunlight, it also increases melting and sea-level rise.[۱۴۹] Limiting new black carbon deposits in the Arctic could reduce global warming by 0.2 °C by 2050.[۱۵۰] The effect of decreasing sulfur content of fuel oil for ships since 2020[۱۵۱] is estimated to cause an additional 0.05 °C increase in global mean temperature by 2050.[۱۵۲]

Solar and volcanic activity

[ویرایش]

As the Sun is the Earth's primary energy source, changes in incoming sunlight directly affect the سامانه اقلیمی زمین.[۱۴۸] چرخه خورشیدی has been measured directly by ماهوارهs,[۱۵۵] and indirect measurements are available from the early 1600s onwards.[۱۴۸] Since 1880, there has been no upward trend in the amount of the Sun's energy reaching the Earth, in contrast to the warming of the lower atmosphere (the تروپوسفر).[۱۵۶] The upper atmosphere (the استراتوسفر) would also be warming if the Sun was sending more energy to Earth, but instead, it has been cooling.[۱۰۴] This is consistent with greenhouse gases preventing heat from leaving the Earth's atmosphere.[۱۵۷]

فوران آتشفشانی can release gases, dust and ash that partially block sunlight and reduce temperatures, or they can send water vapour into the atmosphere, which adds to greenhouse gases and increases temperatures.[۱۵۸] These impacts on temperature only last for several years, because both water vapour and volcanic material have low persistence in the atmosphere.[۱۵۹] گاز آتشفشانی are more persistent, but they are equivalent to less than 1% of current human-caused CO2

emissions.[۱۶۰] Volcanic activity still represents the single largest natural impact (forcing) on temperature in the industrial era. Yet, like the other natural forcings, it has had negligible impacts on global temperature trends since the Industrial Revolution.[۱۵۹]

Climate change feedbacks

[ویرایش]

The climate system's response to an initial forcing is shaped by feedbacks, which either amplify or dampen the change. بازخورد مثبت or positive feedbacks increase the response, while بازخورد منفی or negative feedbacks reduce it.[۱۶۲] The main reinforcing feedbacks are the گاز گلخانهای، the ice–albedo feedback, and the net effect of clouds.[۱۶۳][۱۶۴] The primary balancing mechanism is سرمای تابشی، as Earth's surface gives off more فروسرخ to space in response to rising temperature.[۱۶۵] In addition to temperature feedbacks, there are feedbacks in the carbon cycle, such as the fertilizing effect of CO2

on plant growth.[۱۶۶] Feedbacks are expected to trend in a positive direction as greenhouse gas emissions continue, raising climate sensitivity.[۱۶۷]

These feedback processes alter the pace of global warming. For instance, warmer air رطوبت in the form of بخار آب، which is itself a potent greenhouse gas.[۱۶۳] Warmer air can also make clouds higher and thinner, and therefore more insulating, increasing climate warming.[۱۶۸] The reduction of snow cover and sea ice in the Arctic is another major feedback, this reduces the reflectivity of the Earth's surface in the region and accelerates Arctic warming.[۱۶۹][۱۷۰] This additional warming also contributes to پایایخبندان thawing, which releases methane and CO2

into the atmosphere.[۱۷۱]

Around half of human-caused CO2

emissions have been absorbed by land plants and by the oceans.[۱۷۲] This fraction is not static and if future CO2 emissions decrease, the Earth will be able to absorb up to around 70%. If they increase substantially, it'll still absorb more carbon than now, but the overall fraction will decrease to below 40%.[۱۷۳] This is because climate change increases droughts and heat waves that eventually inhibit plant growth on land, and soils will release more carbon from dead plants when they are warmer.[۱۷۴][۱۷۵] The rate at which oceans absorb atmospheric carbon will be lowered as they become more acidic and experience changes in گردش دماشوری and فیتوپلانکتون distribution.[۱۷۶][۱۷۷][۸۶] Uncertainty over feedbacks, particularly cloud cover,[۱۷۸] is the major reason why different climate models project different magnitudes of warming for a given amount of emissions.[۱۷۹]

Modelling

[ویرایش]

A مدل اقلیمی is a representation of the physical, chemical and biological processes that affect the climate system.[۱۸۰] Models include natural processes like changes in the Earth's orbit, historical changes in the Sun's activity, and volcanic forcing.[۱۸۱] Models are used to estimate the degree of warming future emissions will cause when accounting for the حساسیت به اقلیم.[۱۸۲][۱۸۳] Models also predict the circulation of the oceans, the annual cycle of the seasons, and the flows of carbon between the land surface and the atmosphere.[۱۸۴]

The physical realism of models is tested by examining their ability to simulate current or past climates.[۱۸۵] Past models have underestimated the rate of کاهش دریایخ شمالگان[۱۸۶] and underestimated the rate of precipitation increase.[۱۸۷] Sea level rise since 1990 was underestimated in older models, but more recent models agree well with observations.[۱۸۸] The 2017 United States-published ارزیابی ملی اقلیم notes that "climate models may still be underestimating or missing relevant feedback processes".[۱۸۹] Additionally, climate models may be unable to adequately predict short-term regional climatic shifts.[۱۹۰]

A subset of climate models add societal factors to a physical climate model. These models simulate how population, رشد اقتصادی، and energy use affect—and interact with—the physical climate. With this information, these models can produce scenarios of future greenhouse gas emissions. This is then used as input for physical climate models and carbon cycle models to predict how atmospheric concentrations of greenhouse gases might change.[۱۹۱][۱۹۲] Depending on the socioeconomic scenario and the mitigation scenario, models produce atmospheric CO2

concentrations that range widely between 380 and 1400 ppm.[۱۹۳]

Impacts

[ویرایش]

Environmental effects

[ویرایش]The environmental effects of climate change are broad and far-reaching, تأثیرات تغییرات اقلیمی روی اقیانوسها، ice, and weather. Changes may occur gradually or rapidly. Evidence for these effects comes from studying climate change in the past, from modelling, and from modern observations.[۱۹۴] Since the 1950s, خشکسالیs and heat waves have appeared simultaneously with increasing frequency.[۱۹۵] Extremely wet or dry events within the باد موسمی period have increased in India and East Asia.[۱۹۶] Monsoonal precipitation over the Northern Hemisphere has increased since 1980.[۱۹۷] The rainfall rate and intensity of چرخندهای حارهای و تغییر اقلیم،[۱۹۸] and the geographic range likely expanding poleward in response to climate warming.[۱۹۹] Frequency of tropical cyclones has not increased as a result of climate change.[۲۰۰]

Global sea level is rising as a consequence of انبساط حرارتی and عقبنشینی یخچالهای طبیعی از سال ۱۸۵۰ and یخسار. Sea level rise has increased over time, reaching 4.8 cm per decade between 2014 and 2023.[۲۰۲] Over the 21st century, the IPCC projects 32–62 cm of sea level rise under a low emission scenario, 44–76 cm under an intermediate one and 65–101 cm under a very high emission scenario.[۲۰۳] یخسار processes in Antarctica may add substantially to these values,[۲۰۴] including the possibility of a 2-meter sea level rise by 2100 under high emissions.[۲۰۵]

Climate change has led to decades of کاهش دریایخ شمالگان.[۲۰۶] While ice-free summers are expected to be rare at 1.5 °C degrees of warming, they are set to occur once every three to ten years at a warming level of 2 °C.[۲۰۷] Higher atmospheric CO2

concentrations cause more CO2 to dissolve in the oceans, which is اسیدی شدن اقیانوس.[۲۰۸] Because oxygen is less soluble in warmer water,[۲۰۹] its concentrations in the ocean are decreasing, and پهنه مرده (بومشناسی) are expanding.[۲۱۰]

Tipping points and long-term impacts

[ویرایش]

Greater degrees of global warming increase the risk of passing through 'نقطههای عطف سامانه اقلیمی'—thresholds beyond which certain major impacts can no longer be avoided even if temperatures return to their previous state.[۲۱۳][۲۱۴] For instance, the یخسار گرینلند is already melting, but if global warming reaches levels between 1.7 °C and 2.3 °C, its melting will continue until it fully disappears. If the warming is later reduced to 1.5 °C or less, it will still lose a lot more ice than if the warming was never allowed to reach the threshold in the first place.[۲۱۵] While the ice sheets would melt over millennia, other tipping points would occur faster and give societies less time to respond. The collapse of major جریان اقیانوسیs like the Atlantic meridional overturning circulation (AMOC), and irreversible damage to key ecosystems like the جنگلهای آمازون and صخرههای مرجانی can unfold in a matter of decades.[۲۱۲]

The long-term تأثیرات تغییرات اقلیمی روی اقیانوسها include further ice melt, ocean warming, sea level rise, ocean acidification and ocean deoxygenation.[۲۱۶] The timescale of long-term impacts are centuries to millennia due to CO2 's long atmospheric lifetime.[۲۱۷] The result is an estimated total sea level rise of ۲٫۳ متر بر درجه سلسیوس (۴٫۲ فوت بر درجه فارنهایت) after 2000 years.[۲۱۸] Oceanic CO2

uptake is slow enough that ocean acidification will also continue for hundreds to thousands of years.[۲۱۹] Deep oceans (below ۲٬۰۰۰ متر (۶٬۶۰۰ فوت)) are also already committed to losing over 10% of their dissolved oxygen by the warming which occurred to date.[۲۲۰] Further, the یخسار جنوبگان باختری appears committed to practically irreversible melting, which would increase the sea levels by at least ۳٫۳ متر (۱۰ فوت ۱۰ اینچ) over approximately 2000 years.[۲۱۲][۲۲۱][۲۲۲]

Nature and wildlife

[ویرایش]Recent warming has driven many terrestrial and freshwater species poleward and towards higher فرازا (جغرافیا).[۲۲۳] For instance, the range of hundreds of North American پرندهs has shifted northward at an average rate of 1.5 km/year over the past 55 years.[۲۲۴] Higher atmospheric CO2

levels and an extended growing season have resulted in global greening. However, heatwaves and drought have reduced اکوسیستم productivity in some regions. The future balance of these opposing effects is unclear.[۲۲۵] A related phenomenon driven by climate change is درنوردیدن گیاهان چوبی، affecting up to 500 million hectares globally.[۲۲۶] Climate change has contributed to the expansion of drier climate zones, such as the بیابانزایی in the جنبمدارگان.[۲۲۷] The size and speed of global warming is making آستانه بومشناختی more likely.[۲۲۸] Overall, it is expected that climate change will result in the انقراض of many species.[۲۲۹]

The oceans have heated more slowly than the land, but plants and animals in the ocean have migrated towards the colder poles faster than species on land.[۲۳۰] Just as on land, heat waves in the ocean occur more frequently due to climate change, harming a wide range of organisms such as corals, کتانجک، and پرنده دریایی.[۲۳۱] Ocean acidification makes it harder for کلسیمسازی زیستزاد دریایی such as صدف سیاهs, کشتیچسبs and corals to زیستکانیسازی; and heatwaves have سفیدشدگی مرجان.[۲۳۲] شکوفایی جلبکی زیانبار enhanced by climate change and پرغذایی lower oxygen levels, disrupt شبکه غذاییs and cause great loss of marine life.[۲۳۳] Coastal ecosystems are under particular stress. Almost half of global wetlands have disappeared due to climate change and other human impacts.[۲۳۴] Plants have come under increased stress from damage by insects.[۲۳۵]

|

Humans

[ویرایش]

The effects of climate change are impacting humans everywhere in the world.[۲۴۱] Impacts can be observed on all continents and ocean regions,[۲۴۲] with low-latitude, کشورهای در حال توسعه facing the greatest risk.[۲۴۳] Continued warming has potentially "severe, pervasive and irreversible impacts" for people and ecosystems.[۲۴۴] The risks are unevenly distributed, but are generally greater for disadvantaged people in developing and developed countries.[۲۴۵]

Health and food

[ویرایش]The سازمان جهانی بهداشت calls climate change one of the biggest threats to global health in the 21st century.[۱۴] Scientists have warned about the irreversible harms it poses.[۲۴۶] هوای غیرعادی events affect public health, and امنیت غذایی and امنیت آب.[۲۴۷][۲۴۸][۲۴۹] تأثیرات تغییر اقلیم lead to increased illness and death.[۲۴۷][۲۴۸] Climate change increases the intensity and frequency of extreme weather events.[۲۴۸][۲۴۹] It can affect transmission of عفونت، such as تب دنگی and مالاریا.[۲۴۶][۲۴۷] According to the مجمع جهانی اقتصاد، 14.5 million more deaths are expected due to climate change by 2050.[۲۵۰] 30% of the global population currently live in areas where extreme heat and humidity are already associated with excess deaths.[۲۵۱][۲۵۲] By 2100, 50% to 75% of the global population would live in such areas.[۲۵۱][۲۵۳]

While total بازده محصولs have been increasing in the past 50 years due to agricultural improvements, climate change has already decreased the rate of yield growth.[۲۴۹] Fisheries have been negatively affected in multiple regions.[۲۴۹] While بهرهوری کشاورزی has been positively affected in some high عرض جغرافیایی areas, mid- and low-latitude areas have been negatively affected.[۲۴۹] According to the World Economic Forum, an increase in خشکسالی in certain regions could cause 3.2 million deaths from سوءتغذیه by 2050 and stunting in children.[۲۵۴] With 2 °C warming, global دام (جانور) headcounts could decline by 7–10% by 2050, as less animal feed will be available.[۲۵۵] If the emissions continue to increase for the rest of century, then over 9 million climate-related deaths would occur annually by 2100.[۲۵۶]

Livelihoods and inequality

[ویرایش]Economic damages due to climate change may be severe and there is a chance of disastrous consequences.[۲۵۷] Severe impacts are expected in South-East Asia and sub-Saharan Africa, where most of the local inhabitants are dependent upon natural and agricultural resources.[۲۵۸][۲۵۹] گرمازدگی can prevent outdoor labourers from working. If warming reaches 4 °C then labour capacity in those regions could be reduced by 30 to 50%.[۲۶۰] The بانک جهانی estimates that between 2016 and 2030, climate change could drive over 120 million people into extreme poverty without adaptation.[۲۶۱]

Inequalities based on wealth and social status have worsened due to climate change.[۲۶۲] Major difficulties in mitigating, adapting to, and recovering from climate shocks are faced by marginalized people who have less control over resources.[۲۶۳][۲۵۸] بومیان، who are subsistent on their land and ecosystems, will face endangerment to their wellness and lifestyles due to climate change.[۲۶۴] An expert elicitation concluded that the role of climate change in جنگ has been small compared to factors such as socio-economic inequality and state capabilities.[۲۶۵]

While women are not inherently more at risk from climate change and shocks, limits on women's resources and discriminatory gender norms constrain their adaptive capacity and resilience.[۲۶۶] For example, women's work burdens, including hours worked in agriculture, tend to decline less than men's during climate shocks such as heat stress.[۲۶۶]

Climate migration

[ویرایش]Low-lying islands and coastal communities are threatened by sea level rise, which makes urban flooding more common. Sometimes, land is permanently lost to the sea.[۲۶۷] This could lead to بدون تابعیت for people in island nations, such as the مالدیو and تووالو.[۲۶۸] In some regions, the rise in temperature and humidity may be too severe for humans to adapt to.[۲۶۹] With worst-case climate change, models project that almost one-third of humanity might live in Sahara-like uninhabitable and extremely hot climates.[۲۷۰]

These factors can drive مهاجرت محیط زیستی or مهاجرت اقلیمی، within and between countries.[۱۳] More people are expected to be displaced because of sea level rise, extreme weather and conflict from increased competition over natural resources. Climate change may also increase vulnerability, leading to "trapped populations" who are not able to move due to a lack of resources.[۲۷۱]

|

Reducing and recapturing emissions

[ویرایش]

Climate change can be mitigated by reducing the rate at which greenhouse gases are emitted into the atmosphere, and by increasing the rate at which carbon dioxide is removed from the atmosphere.[۲۷۷] In order to limit global warming to less than 1.5 °C global greenhouse gas emissions needs to be net-zero by 2050, or by 2070 with a 2 °C target.[۲۷۸] This requires far-reaching, systemic changes on an unprecedented scale in energy, land, cities, transport, buildings, and industry.[۲۷۹]

The برنامه محیط زیست سازمان ملل متحد estimates that countries need to triple their pledges under the Paris Agreement within the next decade to limit global warming to 2 °C. An even greater level of reduction is required to meet the 1.5 °C goal.[۲۸۰] With pledges made under the Paris Agreement as of 2024, there would be a 66% chance that global warming is kept under 2.8 °C by the end of the century (range: 1.9–3.7 °C, depending on exact implementation and technological progress). When only considering current policies, this raises to 3.1 °C.[۲۸۱] Globally, limiting warming to ۲ °C may result in higher economic benefits than economic costs.[۲۸۲]

Although there is no single pathway to limit global warming to 1.5 or 2 °C,[۲۸۳] most scenarios and strategies see a major increase in the use of renewable energy in combination with increased energy efficiency measures to generate the needed greenhouse gas reductions.[۲۸۴] To reduce pressures on ecosystems and enhance their carbon sequestration capabilities, changes would also be necessary in agriculture and forestry,[۲۸۵] such as preventing جنگلزدایی and restoring natural ecosystems by بازجنگلکاری.[۲۸۶]

Other approaches to mitigating climate change have a higher level of risk. Scenarios that limit global warming to 1.5 °C typically project the large-scale use of carbon dioxide removal methods over the 21st century.[۲۸۷] There are concerns, though, about over-reliance on these technologies, and environmental impacts.[۲۸۸] Solar radiation modification (SRM) is also a possible supplement to deep reductions in emissions. However, SRM raises significant ethical and legal concerns, and the risks are imperfectly understood.[۲۸۹]

Clean energy

[ویرایش]

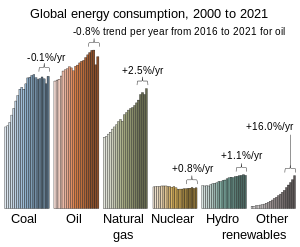

Renewable energy is key to limiting climate change.[۲۹۱] For decades, fossil fuels have accounted for roughly 80% of the world's energy use.[۲۹۲] The remaining share has been split between nuclear power and renewables (including انرژی آبی، زیستانرژی، wind and solar power and انرژی زمینگرمایی).[۲۹۳] Fossil fuel use is expected to peak in absolute terms prior to 2030 and then to decline, with coal use experiencing the sharpest reductions.[۲۹۴] Renewables represented 86% of all new electricity generation installed in 2023.[۲۹۵] Other forms of clean energy, such as nuclear and hydropower, currently have a larger share of the energy supply. However, their future growth forecasts appear limited in comparison.[۲۹۶]

While سامانه فتوولتایی and onshore wind are now among the cheapest forms of adding new power generation capacity in many locations,[۲۹۷] green energy policies are needed to achieve a rapid transition from fossil fuels to renewables.[۲۹۸] To achieve carbon neutrality by 2050, renewable energy would become the dominant form of electricity generation, rising to 85% or more by 2050 in some scenarios. Investment in coal would be eliminated and coal use nearly phased out by 2050.[۲۹۹][۳۰۰]

Electricity generated from renewable sources would also need to become the main energy source for heating and transport.[۳۰۱] Transport can switch away from موتور درونسوز vehicles and towards وسیله نقلیه الکتریکیs, public transit, and active transport (cycling and walking).[۳۰۲][۳۰۳] For shipping and flying, low-carbon fuels would reduce emissions.[۳۰۲] Heating could be increasingly decarbonized with technologies like پمپ حرارتیs.[۳۰۴]

There are obstacles to the continued rapid growth of clean energy, including renewables.[۳۰۵] Wind and solar produce energy انرژی تجدیدپذیر متغیر. Traditionally, نیروگاه تلمبه ذخیرهای and fossil fuel power plants have been used when variable energy production is low. Going forward, battery storage can be expanded, پاسخگویی بار can be matched, and long-distance انتقال انرژی الکتریکی can smooth variability of renewable outputs.[۲۹۱] Bioenergy is often not carbon-neutral and may have negative consequences for food security.[۳۰۶] The growth of nuclear power is constrained by controversy around ضایعات هستهای، پروتکل الحاقی به معاهده منع گسترش سلاحهای هستهای، and accidents.[۳۰۷][۳۰۸] Hydropower growth is limited by the fact that the best sites have been developed, and new projects are confronting increased social and environmental concerns.[۳۰۹]

Low-carbon energy improves human health by minimizing climate change as well as reducing air pollution deaths,[۳۱۰] which were estimated at 7 million annually in 2016.[۳۱۱] Meeting the Paris Agreement goals that limit warming to a 2 °C increase could save about a million of those lives per year by 2050, whereas limiting global warming to 1.5 °C could save millions and simultaneously increase امنیت انرژی and reduce poverty.[۳۱۲] Improving air quality also has economic benefits which may be larger than mitigation costs.[۳۱۳]

Energy conservation

[ویرایش]Reducing energy demand is another major aspect of reducing emissions.[۳۱۴] If less energy is needed, there is more flexibility for clean energy development. It also makes it easier to manage the electricity grid, and minimizes ضریب نشر infrastructure development.[۳۱۵] Major increases in energy efficiency investment will be required to achieve climate goals, comparable to the level of investment in renewable energy.[۳۱۶] Several دنیاگیری کووید-۱۹ related changes in energy use patterns, energy efficiency investments, and funding have made forecasts for this decade more difficult and uncertain.[۳۱۷]

Strategies to reduce energy demand vary by sector. In the transport sector, passengers and freight can switch to more efficient travel modes, such as buses and trains, or use electric vehicles.[۳۱۸] Industrial strategies to reduce energy demand include improving heating systems and motors, designing less energy-intensive products, and increasing product lifetimes.[۳۱۹] In the building sector the focus is on better design of new buildings, and higher levels of energy efficiency in retrofitting.[۳۲۰] The use of technologies like heat pumps can also increase building energy efficiency.[۳۲۱]

Agriculture and industry

[ویرایش]

Agriculture and forestry face a triple challenge of limiting greenhouse gas emissions, preventing the further conversion of forests to agricultural land, and meeting increases in world food demand.[۳۲۲] A set of actions could reduce agriculture and forestry-based emissions by two thirds from 2010 levels. These include reducing growth in demand for food and other agricultural products, increasing land productivity, protecting and restoring forests, and reducing greenhouse gas emissions from agricultural production.[۳۲۳]

On the demand side, a key component of reducing emissions is shifting people towards رژیم گیاهی.[۳۲۴] Eliminating the production of livestock for پیامد زیستمحیطی تولید گوشت would eliminate about 3/4ths of all emissions from agriculture and other land use.[۳۲۵] Livestock also occupy 37% of ice-free land area on Earth and consume feed from the 12% of land area used for crops, driving deforestation and land degradation.[۳۲۶]

Steel and cement production are responsible for about 13% of industrial CO2

emissions. In these industries, carbon-intensive materials such as coke and lime play an integral role in the production, so that reducing CO2 emissions requires research into alternative chemistries.[۳۲۷] Where energy production or CO2

-intensive صنایع سنگین continue to produce waste CO2 , technology can sometimes be used to capture and store most of the gas instead of releasing it to the atmosphere.[۳۲۸] This technology, جداسازی و ذخیرهسازی کربن (CCS), could have a critical but limited role in reducing emissions.[۳۲۸] It is relatively expensive[۳۲۹] and has been deployed only to an extent that removes around 0.1% of annual greenhouse gas emissions.[۳۲۸]

Carbon dioxide removal

[ویرایش]

Natural carbon sinks can be enhanced to sequester significantly larger amounts of CO2

beyond naturally occurring levels.[۳۳۰] Reforestation and جنگلکاری (planting forests where there were none before) are among the most mature sequestration techniques, although the latter raises food security concerns.[۳۳۱] Farmers can promote sequestration of carbon in soils through practices such as use of winter محصول پوششی، reducing the intensity and frequency of خاکورزی، and using compost and manure as soil amendments.[۳۳۲] Forest and landscape restoration yields many benefits for the climate, including greenhouse gas emissions sequestration and reduction.[۱۳۶] Restoration/recreation of coastal wetlands, prairie plots and علفزار دریاییs increases the uptake of carbon into organic matter.[۳۳۳][۳۳۴] When carbon is sequestered in soils and in organic matter such as trees, there is a risk of the carbon being re-released into the atmosphere later through changes in land use, fire, or other changes in ecosystems.[۳۳۵]

The use of bioenergy in conjunction with carbon capture and storage (BECCS) can result in net negative emissions as CO2

is drawn from the atmosphere.[۳۳۶] It remains highly uncertain whether carbon dioxide removal techniques will be able to play a large role in limiting warming to 1.5 °C. Policy decisions that rely on carbon dioxide removal increase the risk of global warming rising beyond international goals.[۳۳۷]

Adaptation

[ویرایش]Adaptation is "the process of adjustment to current or expected changes in climate and its effects".[۳۳۸]: 5 Without additional mitigation, adaptation cannot avert the risk of "severe, widespread and irreversible" impacts.[۳۳۹] More severe climate change requires more transformative adaptation, which can be prohibitively expensive.[۳۴۰] The برد سازگاری is unevenly distributed across different regions and populations, and developing countries generally have less.[۳۴۱] The first two decades of the 21st century saw an increase in adaptive capacity in most low- and middle-income countries with improved access to basic پسابزدایی and electricity, but progress is slow. Many countries have implemented adaptation policies. However, there is a considerable gap between necessary and available finance.[۳۴۲]

Adaptation to sea level rise consists of avoiding at-risk areas, learning to live with increased flooding, and building مهار سیلs. If that fails, managed retreat may be needed.[۳۴۳] There are economic barriers for tackling dangerous heat impact. Avoiding strenuous work or having تهویه مطبوع is not possible for everybody.[۳۴۴] In agriculture, adaptation options include a switch to more sustainable diets, diversification, erosion control, and genetic improvements for increased tolerance to a changing climate.[۳۴۵] Insurance allows for risk-sharing, but is often difficult to get for people on lower incomes.[۳۴۶] Education, migration and سامانه هشدار سریعs can reduce climate vulnerability.[۳۴۷] Planting mangroves or encouraging other coastal vegetation can buffer storms.[۳۴۸][۳۴۹]

Ecosystems adapt to climate change, a process that can be supported by human intervention. By increasing connectivity between ecosystems, species can migrate to more favourable climate conditions. Species can also be introduced to areas acquiring a favourable climate. Protection and restoration of natural and semi-natural areas helps build resilience, making it easier for ecosystems to adapt. Many of the actions that promote adaptation in ecosystems, also help humans adapt via سازگاری بر پایه بومسازگان. For instance, restoration of natural fire regimes makes catastrophic fires less likely, and reduces human exposure. Giving rivers more space allows for more water storage in the natural system, reducing flood risk. Restored forest acts as a carbon sink, but planting trees in unsuitable regions can exacerbate climate impacts.[۳۵۰]

There are همافزایی but also trade-offs between adaptation and mitigation.[۳۵۱] An example for synergy is increased food productivity, which has large benefits for both adaptation and mitigation.[۳۵۲] An example of a trade-off is that increased use of air conditioning allows people to better cope with heat, but increases energy demand. Another trade-off example is that more compact برنامهریزی شهری may reduce emissions from transport and construction, but may also increase the جزیره گرمایی شهری effect, exposing people to heat-related health risks.[۳۵۳]

|

Policies and politics

[ویرایش]

| High | Medium | Low | Very low |

Countries that are most vulnerable to climate change have typically been responsible for a small share of global emissions. This raises questions about justice and fairness.[۳۵۴] Limiting global warming makes it much easier to achieve the UN's سند ۲۰۳۰ یونسکو، such as eradicating poverty and reducing inequalities. The connection is recognized in Sustainable Development Goal 13 which is to "take urgent action to combat climate change and its impacts".[۳۵۵] The goals on food, clean water and ecosystem protection have synergies with climate mitigation.[۳۵۶]

The ژئوپلیتیک of climate change is complex. It has often been framed as a معضل مفتسواری، in which all countries benefit from mitigation done by other countries, but individual countries would lose from switching to a اقتصاد کمکربن themselves. Sometimes mitigation also has localized benefits though. For instance, the benefits of a coal phase-out to public health and local environments exceed the costs in almost all regions.[۳۵۷] Furthermore, net importers of fossil fuels win economically from switching to clean energy, causing net exporters to face stranded assets: fossil fuels they cannot sell.[۳۵۸]

Policy options

[ویرایش]A wide range of خط مشی، مقرراتs, and laws are being used to reduce emissions. As of 2019, قیمت کربن covers about 20% of global greenhouse gas emissions.[۳۵۹] Carbon can be priced with مالیات کربنes and تجارت انتشار کربن.[۳۶۰] Direct global fossil fuel subsidies reached $319 billion in 2017, and $5.2 trillion when indirect costs such as air pollution are priced in.[۳۶۱] Ending these can cause a 28% reduction in global carbon emissions and a 46% reduction in air pollution deaths.[۳۶۲] Money saved on fossil subsidies could be used to support the گذار انرژی instead.[۳۶۳] More direct methods to reduce greenhouse gases include vehicle efficiency standards, renewable fuel standards, and air pollution regulations on heavy industry.[۳۶۴] Several countries استاندارد سبد تجدیدپذیر.[۳۶۵]

Climate justice

[ویرایش]Policy designed through the lens of عدالت اقلیمی tries to address حقوق بشر issues and social inequality. According to proponents of climate justice, the costs of climate adaptation should be paid by those most responsible for climate change, while the beneficiaries of payments should be those suffering impacts. One way this can be addressed in practice is to have wealthy nations pay poorer countries to adapt.[۳۶۶]

Oxfam found that in 2023 the wealthiest 10% of people were responsible for 50% of global emissions, while the bottom 50% were responsible for just 8%.[۳۶۷] Production of emissions is another way to look at responsibility: under that approach, the top 21 fossil fuel companies would owe cumulative climate reparations of $5.4 trillion over the period 2025–2050.[۳۶۸] To achieve a just transition, people working in the fossil fuel sector would also need other jobs, and their communities would need investments.[۳۶۹]

International climate agreements

[ویرایش]

Nearly all countries in the world are parties to the 1994 کنوانسیون چارچوب سازمان ملل متحد درباره تغییر اقلیم (UNFCCC).[۳۷۱] The goal of the UNFCCC is to prevent dangerous human interference with the climate system.[۳۷۲] As stated in the convention, this requires that greenhouse gas concentrations are stabilized in the atmosphere at a level where ecosystems can adapt naturally to climate change, food production is not threatened, and تحلیل اقتصادی تغییرات اقلیمی can be sustained.[۳۷۳] The UNFCCC does not itself restrict emissions but rather provides a framework for protocols that do. Global emissions have risen since the UNFCCC was signed.[۳۷۴] کنفرانس تغییرات اقلیمی سازمان ملل متحد are the stage of global negotiations.[۳۷۵]

The 1997 پیمان کیوتو extended the UNFCCC and included legally binding commitments for most developed countries to limit their emissions.[۳۷۶] During the negotiations, the گروه ۷۷ (representing کشورهای در حال توسعه) pushed for a mandate requiring کشورهای توسعهیافته to "[take] the lead" in reducing their emissions,[۳۷۷] since developed countries contributed most to the انتشار گاز گلخانهای in the atmosphere. Per-capita emissions were also still relatively low in developing countries and developing countries would need to emit more to meet their development needs.[۳۷۸]

The 2009 Copenhagen Accord has been widely portrayed as disappointing because of its low goals, and was rejected by poorer nations including the G77.[۳۷۹] Associated parties aimed to limit the global temperature rise to below 2 °C.[۳۸۰] The Accord set the goal of sending $100 billion per year to developing countries for mitigation and adaptation by 2020, and proposed the founding of the Green Climate Fund.[۳۸۱] تا تاریخ ۲۰۲۰[بروزرسانی], only 83.3 billion were delivered. Only in 2023 the target is expected to be achieved.[۳۸۲]

In 2015 all UN countries negotiated the توافق پاریس، which aims to keep global warming well below 2.0 °C and contains an aspirational goal of keeping warming under ۱٫۵ °C.[۳۸۳] The agreement replaced the Kyoto Protocol. Unlike Kyoto, no binding emission targets were set in the Paris Agreement. Instead, a set of procedures was made binding. Countries have to regularly set ever more ambitious goals and reevaluate these goals every five years.[۳۸۴] The Paris Agreement restated that developing countries must be financially supported.[۳۸۵] تا تاریخ اکتبر ۲۰۲۱[بروزرسانی], 194 states and the اتحادیه اروپا have signed the treaty and 191 states and the EU have تصدیق or acceded to the agreement.[۳۸۶]

The 1987 پیمان مونترال، an international agreement to phase out production of ozone-depleting gases, has had benefits for climate change mitigation.[۳۸۷] Several ozone-depleting gases like کلروفلوئوروکربن are powerful greenhouse gases, so banning their production and usage may have avoided a temperature rise of 0.5 °C–1.0 °C,[۳۸۸] as well as additional warming by preventing damage to vegetation from فرابنفش radiation.[۳۸۹] It is estimated that the agreement has been more effective at curbing greenhouse gas emissions than the Kyoto Protocol specifically designed to do so.[۳۹۰] The most recent amendment to the Montreal Protocol, the 2016 Kigali Amendment, committed to reducing the emissions of hydrofluorocarbons, which served as a replacement for banned ozone-depleting gases and are also potent greenhouse gases.[۳۹۱] Should countries comply with the amendment, a warming of 0.3 °C–0.5 °C is estimated to be avoided.[۳۹۲]

National responses

[ویرایش]

In 2019, the مجلس بریتانیا became the first national government to declare a climate emergency.[۳۹۴] Other countries and حوزه قضاییs followed suit.[۳۹۵] That same year, the پارلمان اروپا declared a "climate and environmental emergency".[۳۹۶] The کمیسیون اروپا presented its European Green Deal with the goal of making the EU carbon-neutral by 2050.[۳۹۷] In 2021, the European Commission released its "Fit for 55" legislation package, which contains guidelines for the صنعت خودروسازی; all new cars on the European market must be خودروهای با آلایندگی صفر from 2035.[۳۹۸]

Major countries in Asia have made similar pledges: South Korea and Japan have committed to become carbon-neutral by 2050, and China by 2060.[۳۹۹] While India has strong incentives for renewables, it also plans a significant expansion of coal in the country.[۴۰۰] Vietnam is among very few coal-dependent, fast-developing countries that pledged to phase out unabated coal power by the 2040s or as soon as possible thereafter.[۴۰۱]

As of 2021, based on information from 48 national climate plans, which represent 40% of the parties to the Paris Agreement, estimated total greenhouse gas emissions will be 0.5% lower compared to 2010 levels, below the 45% or 25% reduction goals to limit global warming to 1.5 °C or 2 °C, respectively.[۴۰۲]

Society

[ویرایش]Denial and misinformation

[ویرایش]

Public debate about climate change has been strongly affected by climate change denial and اطلاعات نادرست، which originated in the United States and has since spread to other countries, particularly Canada and Australia. Climate change denial has originated from fossil fuel companies, industry groups, محافظهکاری think tanks, and contrarian scientists.[۴۰۴] Like the tobacco industry, the main strategy of these groups has been to manufacture doubt about climate-change related scientific data and results.[۴۰۵] People who hold unwarranted doubt about climate change are called climate change "skeptics", although "contrarians" or "deniers" are more appropriate terms.[۴۰۶]

There are different variants of climate denial: some deny that warming takes place at all, some acknowledge warming but attribute it to natural influences, and some minimize the negative impacts of climate change.[۴۰۷] Manufacturing uncertainty about the science later developed into a manufactured controversy: creating the belief that there is significant uncertainty about climate change within the scientific community in order to delay policy changes.[۴۰۸] Strategies to promote these ideas include criticism of scientific institutions,[۴۰۹] and questioning the motives of individual scientists.[۴۰۷] An اتاق پژواک (رسانه) of climate-denying وبلاگ and media has further fomented misunderstanding of climate change.[۴۱۰]

Public awareness and opinion

[ویرایش]

Climate change came to international public attention in the late 1980s.[۴۱۴] Due to media coverage in the early 1990s, people often confused climate change with other environmental issues like ozone depletion.[۴۱۵] In popular culture, the climate fiction movie پسفردا (2004) and the ال گور documentary یک حقیقت ناراحتکننده (2006) focused on climate change.[۴۱۴]

Significant regional, gender, age and political differences exist in both public concern for, and understanding of, climate change. More highly educated people, and in some countries, women and younger people, were more likely to see climate change as a serious threat.[۴۱۶] College biology textbooks from the 2010s featured less content on climate change compared to those from the preceding decade, with decreasing emphasis on solutions.[۴۱۷] Partisan gaps also exist in many countries,[۴۱۸] and countries with high انتشار گاز گلخانهای tend to be less concerned.[۴۱۹] Views on causes of climate change vary widely between countries.[۴۲۰] Concern has increased over time,[۴۲۱] and a majority of citizens in many countries now express a high level of worry about climate change, or view it as a global emergency.[۴۲۲] Higher levels of worry are associated with stronger public support for policies that address climate change.[۴۲۳]

Climate movement

[ویرایش]Climate protests demand that political leaders take action to prevent climate change. They can take the form of public demonstrations, fossil fuel divestment, lawsuits and other activities.[۴۲۴] Prominent demonstrations include the اعتصاب مدارس برای اقلیم. In this initiative, young people across the globe have been protesting since 2018 by skipping school on Fridays, inspired by Swedish teenager گرتا تونبرگ.[۴۲۵] Mass نافرمانی مدنی actions by groups like شورش علیه انقراض have protested by disrupting roads and public transport.[۴۲۶]

Litigation is increasingly used as a tool to strengthen climate action from public institutions and companies. Activists also initiate lawsuits which target governments and demand that they take ambitious action or enforce existing laws on climate change.[۴۲۷] Lawsuits against fossil-fuel companies generally seek compensation for loss and damage.[۴۲۸]

History

[ویرایش]Early discoveries

[ویرایش]

Scientists in the 19th century such as الکساندر فون هومبولت began to foresee the effects of climate change.[۴۳۰][۴۳۱][۴۳۲][۴۳۳] In the 1820s, ژوزف فوریه proposed the greenhouse effect to explain why Earth's temperature was higher than the Sun's energy alone could explain. Earth's atmosphere is transparent to sunlight, so sunlight reaches the surface where it is converted to heat. However, the atmosphere is not transparent to heat radiating from the surface, and captures some of that heat, which in turn warms the planet.[۴۳۴]

In 1856 یونیس نیوتن فوت demonstrated that the warming effect of the Sun is greater for air with water vapour than for dry air, and that the effect is even greater with carbon dioxide (CO2 ). She concluded that "An atmosphere of that gas would give to our earth a high temperature..."[۴۳۵][۴۳۶]

Starting in 1859,[۴۳۷] جان تیندال established that nitrogen and oxygen—together totalling 99% of dry air—are transparent to radiated heat. However, water vapour and gases such as methane and carbon dioxide absorb radiated heat and re-radiate that heat into the atmosphere. Tyndall proposed that changes in the concentrations of these gases may have caused climatic changes in the past, including عصر یخبندانs.[۴۳۸]

سوانته آرنیوس noted that water vapour in air continuously varied, but the CO2

concentration in air was influenced by long-term geological processes. Warming from increased CO2 levels would increase the amount of water vapour, amplifying warming in a positive feedback loop. In 1896, he published the first مدل اقلیمی of its kind, projecting that halving CO2 levels could have produced a drop in temperature initiating an ice age. Arrhenius calculated the temperature increase expected from doubling CO2 to be around 5–6 °C.[۴۳۹] Other scientists were initially sceptical and believed that the greenhouse effect was saturated so that adding more CO2 would make no difference, and that the climate would be self-regulating.[۴۴۰] Beginning in 1938, Guy Stewart Callendar published evidence that climate was warming and CO2 levels were rising,[۴۴۱] but his calculations met the same objections.[۴۴۰]

Development of a scientific consensus

[ویرایش]

In the 1950s, گیلبرت پلاس created a detailed computer model that included different atmospheric layers and the infrared spectrum. This model predicted that increasing CO2

levels would cause warming. Around the same time, Hans Suess found evidence that CO2 levels had been rising, and راجر ریول showed that the oceans would not absorb the increase. The two scientists subsequently helped چارلز دیوید کیلینگ to begin a record of continued increase, which has been termed the "Keeling Curve".[۴۴۰] Scientists alerted the public,[۴۴۶] and the dangers were highlighted at James Hansen's 1988 Congressional testimony.[۳۸] The هیئت بیندولتی تغییر اقلیم (IPCC), set up in 1988 to provide formal advice to the world's governments, spurred مطالعات میانرشتهای.[۴۴۷] As part of the هیئت بیندولتی تغییر اقلیم، scientists assess the scientific discussion that takes place in داوری همتا نشریه علمی articles.[۴۴۸]

There is a near-complete scientific consensus that the climate is warming and that this is caused by human activities. As of 2019, agreement in recent literature reached over 99%.[۴۴۳][۴۴۴] No scientific body of national or international standing اجماع علمی درباره تغییر اقلیم.[۴۴۹] Consensus has further developed that some form of action should be taken to protect people against the impacts of climate change. National science academies have called on world leaders to cut global emissions.[۴۵۰] The 2021 IPCC Assessment Report stated that it is "unequivocal" that climate change is caused by humans.[۴۴۴]

جستارهای وابسته

[ویرایش]- آنتروپوسن – فاصله زمانی زمینشناسی پیشنهادی که در آن انسانها تأثیرات زمینشناسی قابلتوجهی دارند.

منابع

[ویرایش]- ↑ "GISS Surface Temperature Analysis (v4)". NASA. Retrieved 12 January 2024.

- ↑ (IPCC AR6 WG1 2021، SPM-7)

- ↑ (IPCC SR15 Ch1 2018، ص. 54): "These global-level rates of human-driven change far exceed the rates of change driven by geophysical or biosphere forces that have altered the Earth System trajectory in the past (e.g. , Summerhayes, 2015; Foster et al. , 2017); even abrupt geophysical events do not approach current rates of human-driven change."

- ↑ ۴٫۰ ۴٫۱ Lynas, Mark; Houlton, Benjamin Z.; Perry, Simon (19 October 2021). "Greater than 99% consensus on human caused climate change in the peer-reviewed scientific literature". Environmental Research Letters. 16 (11): 114005. Bibcode:2021ERL....16k4005L. doi:10.1088/1748-9326/ac2966. ISSN 1748-9326. S2CID 239032360.

- ↑ ۵٫۰ ۵٫۱ (Our World in Data, 18 September 2020)

- ↑ (IPCC AR6 WG1 Technical Summary 2021، ص. 67): "Concentrations of CO2 , methane (الگو:CH4), and nitrous oxide (الگو:N2O) have increased to levels unprecedented in at least 800,000 years, and there is high confidence that current CO2 concentrations have not been experienced for at least 2 million years."

- ↑ (IPCC SRCCL 2019، ص. 7): "Since the pre-industrial period, the land surface air temperature has risen nearly twice as much as the global average temperature (high confidence). Climate change... contributed to desertification and land degradation in many regions (high confidence)."

- ↑ (IPCC SRCCL 2019، ص. 45): "Climate change is playing an increasing role in determining wildfire regimes alongside human activity (medium confidence), with future climate variability expected to enhance the risk and severity of wildfires in many biomes such as tropical rainforests (high confidence)."

- ↑ (IPCC SROCC 2019، ص. 16): "Over the last decades, global warming has led to widespread shrinking of the cryosphere, with mass loss from ice sheets and glaciers (very high confidence), reductions in snow cover (high confidence) and Arctic sea ice extent and thickness (very high confidence), and increased permafrost temperature (very high confidence)."

- ↑ (IPCC AR6 WG1 Ch11 2021، ص. 1517)

- ↑ EPA (19 January 2017). "Climate Impacts on Ecosystems". Archived from the original on 27 January 2018. Retrieved 5 February 2019.

Mountain and arctic ecosystems and species are particularly sensitive to climate change... As ocean temperatures warm and the acidity of the ocean increases, bleaching and coral die-offs are likely to become more frequent.

- ↑ (IPCC SR15 Ch1 2018، ص. 64): "Sustained net zero anthropogenic emissions of CO2 and declining net anthropogenic non-CO2 radiative forcing over a multi-decade period would halt anthropogenic global warming over that period, although it would not halt sea level rise or many other aspects of climate system adjustment."

- ↑ ۱۳٫۰ ۱۳٫۱ (Cattaneo و دیگران 2019); (IPCC AR6 WG2 2022، صص. 15, 53)

- ↑ ۱۴٫۰ ۱۴٫۱ (WHO, Nov 2023)

- ↑ (IPCC AR6 WG2 2022، ص. 19)

- ↑ (IPCC AR6 WG2 2022، صص. 21–26; 2504)

- ↑ (IPCC AR6 SYR SPM 2023، صص. 8–9): "Effectiveness15 of adaptation in reducing climate risks16

- ↑ Tietjen, Bethany (2 November 2022). "Loss and damage: Who is responsible when climate change harms the world's poorest countries?". The Conversation. Retrieved 30 August 2023.

- ↑ "Climate Change 2022: Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability". هیئت بیندولتی تغییر اقلیم. 27 February 2022. Retrieved 30 August 2023.

- ↑ Ivanova, Irina (June 2, 2022). "California is rationing water amid its worst drought in 1,200 years". سیبیاس نیوز.

- ↑ Poynting, Mark; Rivault, Erwan (10 January 2024). "2023 confirmed as world's hottest year on record". بیبیسی. Retrieved 13 January 2024.

- ↑ "Human, economic, environmental toll of climate change on the rise: WMO | UN News". news.un.org (به انگلیسی). 21 April 2023. Retrieved 11 April 2024.

- ↑ (IPCC AR6 WG1 Technical Summary 2021، ص. 71)

- ↑ ۲۴٫۰ ۲۴٫۱ (United Nations Environment Programme 2024، ص. XVIII): "The full implementation and continuation of the level of mitigation effort implied by unconditional or conditional NDC scenarios lower these projections to 2.8 °C (range: 1.9–3.7) and 2.6 °C (range: 1.9–3.6), respectively. All with at least a 66 per cent chance."

- ↑ (IPCC SR15 Ch2 2018، صص. 95–96): "In model pathways with no or limited overshoot of 1.5 °C, global net anthropogenic CO2 emissions decline by about 45% from 2010 levels by 2030 (40–60% interquartile range), reaching net zero around 2050 (2045–2055 interquartile range)"

- ↑ (IPCC SR15 2018، ص. 17، SPM C.3): "All pathways that limit global warming to 1.5 °C with limited or no overshoot project the use of carbon dioxide removal (CDR) on the order of 100–1000 GtCO2 over the 21st century. CDR would be used to compensate for residual emissions and, in most cases, achieve net negative emissions to return global warming to 1.5 °C following a peak (high confidence). CDR deployment of several hundreds of GtCO2 is subject to multiple feasibility and sustainability constraints (high confidence)."

- ↑ (IPCC AR5 WG3 Annex III 2014، ص. 1335)

- ↑ (IPCC AR6 WG3 2022، صص. 24–25; 89)

- ↑ (IPCC AR6 WG3 2022، ص. 84): "Stringent emissions reductions at the level required for 2°C or 1.5°C are achieved through the increased electrification of buildings, transport, and industry, consequently all pathways entail increased electricity generation (high confidence)."

- ↑ ۳۰٫۰ ۳۰٫۱ (IPCC SRCCL Summary for Policymakers 2019، ص. 18)

- ↑ (IPCC AR6 WG3 2022، صص. 24–25; 114)

- ↑ ۳۲٫۰ ۳۲٫۱ (NASA, 5 December 2008).

- ↑ (NASA, 7 July 2020)

- ↑ (Shaftel 2016): " 'Climate change' and 'global warming' are often used interchangeably but have distinct meanings. ... Global warming refers to the upward temperature trend across the entire Earth since the early 20th century ... Climate change refers to a broad range of global phenomena ...[which] include the increased temperature trends described by global warming."

- ↑ (Associated Press, 22 September 2015): "The terms global warming and climate change can be used interchangeably. Climate change is more accurate scientifically to describe the various effects of greenhouse gases on the world because it includes extreme weather, storms and changes in rainfall patterns, ocean acidification and sea level.".

- ↑ (IPCC AR5 SYR Glossary 2014، ص. 120): "Climate change refers to a change in the state of the climate that can be identified (e.g. , by using statistical tests) by changes in the mean and/or the variability of its properties and that persists for an extended period, typically decades or longer. Climate change may be due to natural internal processes or external forcings such as modulations of the solar cycles, volcanic eruptions and persistent anthropogenic changes in the composition of the atmosphere or in land use."

- ↑ Broeker, Wallace S. (8 August 1975). "Climatic Change: Are We on the Brink of a Pronounced Global Warming?". ساینس (مجله). 189 (4201): 460–463. Bibcode:1975Sci...189..460B. doi:10.1126/science.189.4201.460. JSTOR 1740491. PMID 17781884. S2CID 16702835.

- ↑ ۳۸٫۰ ۳۸٫۱ (Weart "The Public and Climate Change: The Summer of 1988"), "News reporters gave only a little attention ...".

- ↑ (Joo و دیگران 2015).

- ↑ (Hodder و Martin 2009)

- ↑ (BBC Science Focus Magazine, 3 February 2020)

- ↑ (Neukom و دیگران 2019b).

- ↑ "Global Annual Mean Surface Air Temperature Change". ناسا. Retrieved 23 February 2020.

- ↑ IPCC AR6 WG1 Ch2 2021, pp. 294, 296.

- ↑ IPCC AR6 WG1 Ch2 2021, p. 366.

- ↑ Marcott, S. A.; Shakun, J. D.; Clark, P. U.; Mix, A. C. (2013). "A reconstruction of regional and global temperature for the past 11,300 years". Science. 339 (6124): 1198–1201. Bibcode:2013Sci...339.1198M. doi:10.1126/science.1228026. PMID 23471405.

- ↑ IPCC AR6 WG1 Ch2 2021, p. 296.

- ↑ (IPCC AR5 WG1 Ch5 2013، ص. 386)

- ↑ (Neukom و دیگران 2019a)

- ↑ (IPCC SR15 Ch1 2018، ص. 57): "This report adopts the 51-year reference period, 1850–1900 inclusive, assessed as an approximation of pre-industrial levels in AR5 ... Temperatures rose by 0.0 °C–0.2 °C from 1720–1800 to 1850–1900"

- ↑ (Hawkins و دیگران 2017، ص. 1844)

- ↑ "Mean Monthly Temperature Records Across the Globe / Timeseries of Global Land and Ocean Areas at Record Levels for September from 1951-2023". NCEI.NOAA.gov. National Centers for Environmental Information (NCEI) of the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA). September 2023. Archived from the original on 14 October 2023. (change "202309" in URL to see years other than 2023, and months other than 09=September)

- ↑ Top 700 meters: Lindsey, Rebecca; Dahlman, Luann (6 September 2023). "Climate Change: Ocean Heat Content". climate.gov. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA). Archived from the original on 29 October 2023. ● Top 2000 meters: "Ocean Warming / Latest Measurement: December 2022 / 345 (± 2) zettajoules since 1955". NASA.gov. National Aeronautics and Space Administration. Archived from the original on 20 October 2023.

- ↑ (IPCC AR5 WG1 Summary for Policymakers 2013، صص. 4–5): "Global-scale observations from the instrumental era began in the mid-19th century for temperature and other variables ... the period 1880 to 2012 ... multiple independently produced datasets exist."

- ↑ Mooney, Chris; Osaka, Shannon (26 December 2023). "Is climate change speeding up? Here's what the science says". The Washington Post. Retrieved 18 January 2024.

- ↑ ۵۶٫۰ ۵۶٫۱ "Global 'Sunscreen' Has Likely Thinned, Report NASA Scientists". ناسا. 15 March 2007.

- ↑ ۵۷٫۰ ۵۷٫۱ ۵۷٫۲ Quaas, Johannes; Jia, Hailing; Smith, Chris; Albright, Anna Lea; Aas, Wenche; Bellouin, Nicolas; Boucher, Olivier; Doutriaux-Boucher, Marie; Forster, Piers M.; Grosvenor, Daniel; Jenkins, Stuart; Klimont, Zbigniew; Loeb, Norman G.; Ma, Xiaoyan; Naik, Vaishali; Paulot, Fabien; Stier, Philip; Wild, Martin; Myhre, Gunnar; Schulz, Michael (21 September 2022). "Robust evidence for reversal of the trend in aerosol effective climate forcing". Atmospheric Chemistry and Physics (به انگلیسی). 22 (18): 12221–12239. Bibcode:2022ACP....2212221Q. doi:10.5194/acp-22-12221-2022. hdl:20.500.11850/572791. S2CID 252446168.

- ↑ (IPCC AR6 WG1 2021، ص. 43)

- ↑ (EPA 2016): "The U.S. Global Change Research Program, the National Academy of Sciences, and the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) have each independently concluded that warming of the climate system in recent decades is "unequivocal". This conclusion is not drawn from any one source of data but is based on multiple lines of evidence, including three worldwide temperature datasets showing nearly identical warming trends as well as numerous other independent indicators of global warming (e.g. rising sea levels, shrinking Arctic sea ice)."

- ↑ (IPCC SR15 Ch1 2018، ص. 81).

- ↑ (Forster و دیگران 2024، ص. 2626)

- ↑ Samset, B. H.; Fuglestvedt, J. S.; Lund, M. T. (7 July 2020). "Delayed emergence of a global temperature response after emission mitigation". Nature Communications. 11 (1): 3261. Bibcode:2020NatCo..11.3261S. doi:10.1038/s41467-020-17001-1. hdl:11250/2771093. PMC 7341748. PMID 32636367.

At the time of writing, that translated into 2035–2045, where the delay was mostly due to the impacts of the around 0.2 °C of natural, interannual variability of global mean surface air temperature

- ↑ Seip, Knut L.; Grøn, ø.; Wang, H. (31 August 2023). "Global lead-lag changes between climate variability series coincide with major phase shifts in the Pacific decadal oscillation". Theoretical and Applied Climatology (به انگلیسی). 154 (3–4): 1137–1149. Bibcode:2023ThApC.154.1137S. doi:10.1007/s00704-023-04617-8. hdl:11250/3088837. ISSN 0177-798X. S2CID 261438532.

- ↑ Yao, Shuai-Lei; Huang, Gang; Wu, Ren-Guang; Qu, Xia (January 2016). "The global warming hiatus—a natural product of interactions of a secular warming trend and a multi-decadal oscillation". Theoretical and Applied Climatology (به انگلیسی). 123 (1–2): 349–360. Bibcode:2016ThApC.123..349Y. doi:10.1007/s00704-014-1358-x. ISSN 0177-798X. S2CID 123602825. Retrieved 20 September 2023.

- ↑ Xie, Shang-Ping; Kosaka, Yu (June 2017). "What Caused the Global Surface Warming Hiatus of 1998–2013?". Current Climate Change Reports (به انگلیسی). 3 (2): 128–140. Bibcode:2017CCCR....3..128X. doi:10.1007/s40641-017-0063-0. ISSN 2198-6061. S2CID 133522627. Retrieved 20 September 2023.

- ↑ "Global temperature exceeds 2 °C above pre-industrial average on 17 November". برنامه کوپرنیک. 21 November 2023. Retrieved 31 January 2024.

While exceeding the 2 °C threshold for a number of days does not mean that we have breached the Paris Agreement targets, the more often that we exceed this threshold, the more serious the cumulative effects of these breaches will become.

- ↑ IPCC, 2021: Summary for Policymakers. In: Climate Change 2021: The Physical Science Basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change [Masson-Delmotte, V., P. Zhai, A. Pirani, S.L. Connors, C. Péan, S. Berger, N. Caud, Y. Chen, L. Goldfarb, M. I. Gomis, M. Huang, K. Leitzell, E. Lonnoy, J. B. R. Matthews, T. K. Maycock, T. Waterfield, O. Yelekçi, R. Yu, and B. Zhou (eds.)]. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, United Kingdom and New York, New York, US, pp. 3−32, doi:10.1017/9781009157896.001.

- ↑ McGrath, Matt (17 May 2023). "Global warming set to break key 1.5C limit for first time". بیبیسی نیوز. Retrieved 31 January 2024.

The researchers stress that temperatures would have to stay at or above 1.5C for 20 years to be able to say the Paris agreement threshold had been passed.

- ↑ (Kennedy و دیگران 2010، ص. S26). Figure 2.5.

- ↑ Loeb et al. 2021.

- ↑ "Global Warming". آزمایشگاه پیشرانش جت. 3 June 2010. Retrieved 11 September 2020.

Satellite measurements show warming in the troposphere but cooling in the stratosphere. This vertical pattern is consistent with global warming due to increasing greenhouse gases but inconsistent with warming from natural causes.

- ↑ (Kennedy و دیگران 2010، صص. S26, S59–S60)

- ↑ (USGCRP Chapter 1 2017، ص. 35)

- ↑ (IPCC AR6 WG2 2022، صص. 257–260)

- ↑ (IPCC SRCCL Summary for Policymakers 2019، ص. 7)

- ↑ (Sutton، Dong و Gregory 2007).

- ↑ "Climate Change: Ocean Heat Content". Noaa Climate.gov. اداره ملی اقیانوسی و جوی. 2018. Archived from the original on 12 February 2019. Retrieved 20 February 2019.

- ↑ (IPCC AR5 WG1 Ch3 2013، ص. 257): "افزایش سطح آب دریاها dominates the global energy change inventory. Warming of the ocean accounts for about 93% of the increase in the Earth's energy inventory between 1971 and 2010 (high confidence), with warming of the upper (0 to 700 m) ocean accounting for about 64% of the total.

- ↑ von Schuckman, K.; Cheng, L.; Palmer, M. D.; Hansen, J.; et al. (7 September 2020). "Heat stored in the Earth system: where does the energy go?". Earth System Science Data. 12 (3): 2013–2041. Bibcode:2020ESSD...12.2013V. doi:10.5194/essd-12-2013-2020. hdl:20.500.11850/443809.

- ↑ (NOAA, 10 July 2011).

- ↑ (United States Environmental Protection Agency 2016، ص. 5): "Black carbon that is deposited on snow and ice darkens those surfaces and decreases their reflectivity (albedo). This is known as the snow/ice albedo effect. This effect results in the increased absorption of radiation that accelerates melting."

- ↑ "Arctic warming three times faster than the planet, report warns". فیز دات ارگ (به انگلیسی). 20 May 2021. Retrieved 6 October 2022.

- ↑ Rantanen, Mika; Karpechko, Alexey Yu; Lipponen, Antti; Nordling, Kalle; Hyvärinen, Otto; Ruosteenoja, Kimmo; Vihma, Timo; Laaksonen, Ari (11 August 2022). "The Arctic has warmed nearly four times faster than the globe since 1979". Communications Earth & Environment (به انگلیسی). 3 (1): 168. Bibcode:2022ComEE...3..168R. doi:10.1038/s43247-022-00498-3. hdl:11250/3115996. ISSN 2662-4435. S2CID 251498876.

- ↑ "The Arctic is warming four times faster than the rest of the world" (به انگلیسی). 14 December 2021. Retrieved 6 October 2022.